There’s a nice article about British hedges (which quotes from Hedge Britannia, as well as the classic Hedges, by Pollard, Moore and Hooper) at woodlands.co.uk – you can link to it here.

Category Archives: Rural Britain

Ravilious Hedges

My mum sent me this card – I love Eric Ravilious’ pictures and this is a nice one that includes a hedgerown (although it looks a bit gappy or lollypopped).

Filed under Historical Hedges, Rural Britain

Incredible Edible Todmorden – what a great idea

I’m very impressed by the Incredible Edible initiative in Todmorden (and elsewhere), where they are planting food in public places for anyone to eat. Well worth a look at their website.

Filed under Hedge Politics, Rural Britain

Britishness and the Hedge (and Burgess Hill)

I’m in Burgess Hill, the town where I grew up. The last of my family moved away over twenty years ago and I have lost touch with most people I knew here. It is a dormitory town, an hour from London and fifteen minutes from Brighton on the mainline. There wasn’t really a proper village here before the railway came – nearby villages such as Ditchling, Lindfield, Cuckfield, and Wivelsfield didn’t want any truck with newfangled railways so the line bypassed them, and a town grew up around the station.

It doesn’t seem to have changed much since I left. The iron bolts on the railway bridge look the same, although the station itself has had a lick of paint. At the highest point of the town, the Top House pub is still there with an old oak tree on its steps. I walk down Silverdale Road, past the house I was born in, and further along to the house we lived in when I was about ten years old.

It was a marvellous, big old detached house, which my father could barely afford in the first place. At the side, there was a rickety greenhouse with a mangle, strange old pots of chemicals and clay planters, and a slightly mouldy croquet set. Inside the house it was cold and draughty, there were squirrels (or possibly rats) scampering in the rafters, and a pervasive smell of gently rotting garden apples, as we usually attempted to store windfalls through the winter in a unplumbed bathroom. There were also redcurrant and blackcurrant bushes and wild strawberries growing under the hedges beside the old garage.

It’s a house I often return to in dreams, perhaps because I lived here at an impressionable age. Today, everything about it looks smaller to me, and the ramshackle edges have been cleaned up in subsequent renovations. The only thing which doesn’t look like a miniature, tidied-up version of my childhood is the laurel hedge at the front which I used to trim.

To my delight, it has grown to a gargantuan, messy height, and sprawls across the pavement in a manner that would have appalled our 1970s neighbours. It is not of Leylandiian proportions, but it is in its own way a beautiful monster of a hedge.

While writing and researching my book on hedges, I have been pondering the role that hedges and hedgerows played in the creation of Britain, but I’m still not sure that I know what Britishness is. National identity grows out of our sense of territory and tribalism, which starts from our immediate surroundings. So at least part of what my country means to me must have come from my childhood and the things I discovered about the world as I grew up among the hedges of Burgess Hill.

So what did I learn?

I learned that a ball going over the hedge might never be returned. I learned the importance of keeping your hedge well-clipped. I learned that neighbours can be friendly, but more often like to keep themselves to themselves, in the privacy of their own space. I saw the wide disparity in the spaces in which people had to live. And I learned that hedge topiary was a slightly eccentric habit, but nonetheless within the bounds of social acceptability.

I also came to see that fields, trees and hedges were not just part of nature, but objects with historical resonance. Many roads in this part of town are named after trees or the landscape they replaced. Ferndale, Birchwood Grove, Glendale, Ravenswood, Woodland Drive. These are wide leafy roads, with plenty of trees remaining, but they were once woodland or fields leading down the hill to Ditchling Common, where the local commoners had had grazing rights. We used to walk there via the abandoned One o’Clock Farm. It was a lovely route, through overgrown fields, past hedgerows full of wild flowers, and a few derelict farm buildings sinking gracefully into disrepair. When the land was eventually sold to developers to become a housing estate, we hated the builders as they concreted it over, field by field. But still we could cycle to countryside beyond, or drive up to the South Downs where the footpaths passed Iron Age forts and looked down on the patchwork fields of Sussex below.

Nationality is about what we think of as normal, as part of “us” rather than “them”. The landscape around us is important not just because it is a familiar scene that we get accustomed to, but also because we feel that it somehow belongs to us. As a key element in the transformation from wilderness to the modern landscape, the hedges of town and country tell us a great deal about the ideas that shaped our nation.

In exploring the roots and history of the British hedge, I’ve been tracing unbroken lines that stretch back into the past. These lines make a web that criss-crosses the country, partly structured but with much of its form owing to natural growth, tendrils looping out and back again, composed of the new growth of personal recollection on the ‘dead hedges’ of those who’ve gone before.

I think this is where Britishness lies for me, somewhere in that great constantly changing hedge of different roots, in the growth and regrowth that has led us to where we are today and will lead us into the future.

Filed under Historical Hedges, Rural Britain, The Hedge Philosopher

Hedgewalking – lovely illustrated walk, Hermitage blog

Just to link to this lovely series of pictures (and descriptions) of the hedgerows in lanes and fields close to the edge of Dartmoor, from the Hermitage blog.

Well worth a look especially if, like me, you are stuck somewhere a bit more urban and feel like taking a bit of vicarious pleasure in the countryside, as seen through someone else’s eyes…

Filed under Everyday Hedges, Rural Britain

Requiem for Cowm Top

I spent Wednesday afternoon being walked up and down muddy lanes in Rochdale by my wife. Rather than consulting a map she had decided to trust to some rather distant childhood memories of the route, so it took a while before we found the right path, which was the one leading to Cowm Top.

I need to explain a bit of background here. My wife grew up in Rochdale, which is a complicated town. It used to be the wealthiest town in the North West, when the mills were providing constant employment and there were engineering firms and other small industrial enterprises all over town. Now the mills are closed, along with most of the industry and, while wealthy pockets like Bamford remain, the town is pretty run-down and tends to make the news only when they want an example of an estate with high unemployment or a closed down high street. It also has a problem common in the mill towns, resulting from the immigration in the 1960s (to fill the many jobs that still existed). As a result of the specific local circumstances this has led to a situation where there is a large white working class population and also a large Asian working class population, but the two are not at all well-integrated, both have problems with employment, housing and so on, so there is some hostility between the two, more than you find in cities where immigration has been more incremental over longer periods.

Rochdale is surrounded by the moors – it lies below Saddleworth to the east and is close to scenic parts of the Pennines such as Blackstone Edge. It also has surprisingly rural outskirts. My wife spent a lot of time with her grandparents as a child – they lived on Malcolm St, off Queensway (which is a rather grim line of mills along the canal at that point). At the end of the short terraced street, you could walk straight up into the fields of Cowm Top, a pretty hilly area, and watch rabbits, walk the hedgerows looking for birds’ nests and so on, and she was often up there with her grandad.

There have been some major changes since then. Firstly, the M62 was driven through the area in the early seventies. The planning juggernaut driving this road through (against a lot of local opposition) was pretty unstoppable – one poor farmer on the Yorkshire side was left with the twin lanes of the motorway spitefully hemming in his land when he failed to comply. It doesn’t go across Cowm Top, but it is close by, running alongside Kirkholt, and the the noise is inescapable. It is still widely hated in the area.

Secondly, an industrial estate was built at the end of Malcolm Street, blocking off the residents’ direct access to Cowm Top. Which is why we were wandering the muddy lanes.

We started at Thornham Church, where her grandparents are buried. Here you have some lovely rural views, looking up towards Tandle Hill. Then after a few false starts, we went up Trows Lane. This leads to an old mill and millpond, now back in use as an auto works and fishing pond. From there, Sandy Lane leads up to Cowm Top – it used to be a wider green lane, now there is a road adjacent so it is hemmed in by the back gardens. It is still a rather lovely little walk, as you come out to the hilly ground of Cowm Top, by the rabbit hill and an overgrown allotment, and a field of friendly horses from the local stables. At the top there is a crossroads, with both footpaths showing the signs of antiquiy – a deep path running through a holloway between banks with old hedgerows, with a wide variety of species suggesting they have been in use for a long time (although they are neglected and overgrown today). Rochdale has been a town since the 12th century at least and there is no reason to believe these paths haven’t been there for much of that time.

The top of the hill is rather sad though. As the motorway noise increases, so does the encroachment from the industrial estate. A few years ago a campaign was fought (and lost) to prevent further development, either by buying the land or having it declared a village green. It was certainly in use as common land for centuries, but it was denied this protection and now there are more monstrous warehouses being built up the side of the hill. So it was with mixed emotions that my wife revisited this particular childhood memory.

One particular reason to mourn this vandalistic piece of planning is that Rochdale is a town full of brown field development opportunities – old mills and factories where there is no rural beauty to destroy. In theory we are supposed to be encouraging brown field development over green field. But while many developers have just taken advantage of loopholes to build on playing fields and back gardens (both ludicrously categorised as “brown field”), elsewhere this kind of destruction continues.

Not all development can be avoided, of course, but this is a good example of a situation where the supposed goal of avoiding green field destruction in favour of brown field development has spectacularly failed. Cowm Top is still a nice place, but it will never again be the place my wife remembers.

Filed under Hedge Politics, Rural Britain

Another Hedge of Many Species

This one is from Eaglescarnie Mains, a farm in East Lothian, run by Michael and Barbara Williams, also photos from my mum. It’s at least a couple of centuries old, going from maps, but given the variety of species it contains (including a bit of oak and horse chestnut) it may well be rather older than that.

Filed under Everyday Hedges, Hedges and Biodiversity, Rural Britain

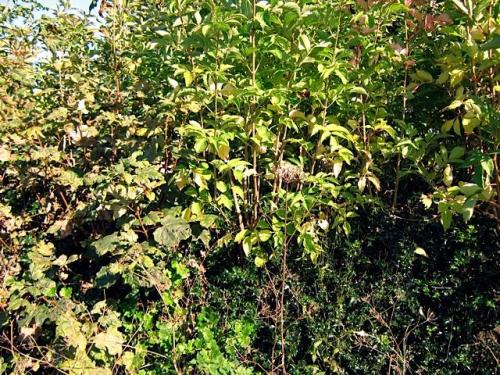

A Hedge of Many Species

As I keep mentioning, hedges have a valuable role to play in biodiversity, as they contain such a wide variety of flora and fauna, and provide cover and nutrition for many small animals, whether they be bird, mammal, insect or reptile.

The older the hedge, the more plant species it tends to contain (I’ve posted previously about Hooper’s Law which gives us a way of estimating the age of a hedge based on the number of woody species it contains). Here’s an example my mother found and photographed, a single rural hedgerow in Surrey (near Merrow), showing a wide range of species (with her identifications below):

Sycamore

Beech, viburnum, possibly some privet

Holly, sycamore

Berberis and ivy as well

Possibly some hazel…

And a bit more holly.

Of course that’s before you start looking at the plants at ground level, which are also often fascinatingly diverse, and again can tell us something about the age of a hedge (woodland plants tend to indicate an ancient hedge that was originally created as a remnant when the forest was cleared).

Filed under Everyday Hedges, Hedges and Biodiversity, Rural Britain

Hedges and bees – and the future of our crops

There is a good article in the Guardian (here) about research done by Northampton University’s Landscape and Biodiversity Research Group showing that bees use hedgerows to navigate around the countryside.

Of course we already know how crucial bees are for pollinating crops in general, and how disastrous it will be if our bee populations continue to fall. It may provide a lot of low-wage employment if we have to hand-polliinate our future crops, but large parts of our food chain are at risk if we lose the pollinating insects. It is also well known that hedges provide a good environment for insects, bees, and mammals and birds (who are often drawn there by the aforementioned flying and crawling animals as well as by the ground cover).

But it is fascinating to have proof that bees also use hedges as navigation routes. This is significant because it has also been shown that flowering plants close to hedges are more succesful at reproducing (especially those near to a meeting point of hedgerows). It’s yet more proof that the role of hedges in our landscape goes way beyond their heritage and aesthetic importance.

Filed under Hedges and Biodiversity, Rural Britain